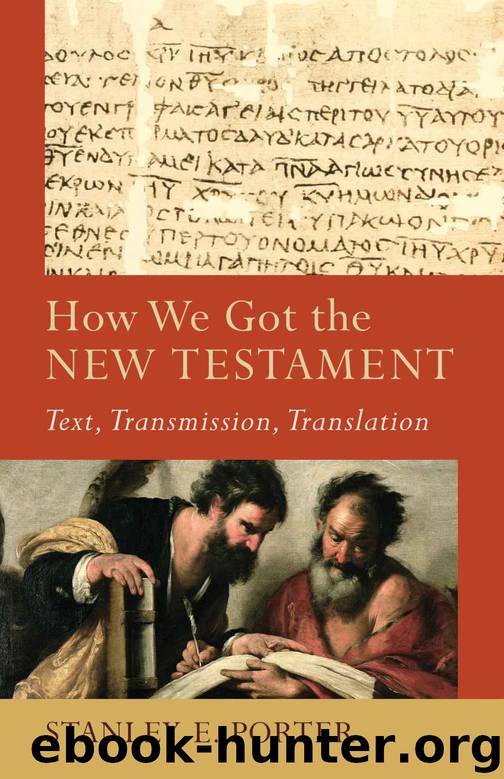

How We Got the New Testament (): Text, Transmission, Translation (Acadia Studies in Bible and Theology) by Stanley E. Porter

Author:Stanley E. Porter [Porter, Stanley E.]

Language: ell

Format: mobi

Tags: REL006080, Bible. New Testament—History, REL006400

ISBN: 9781441242686

Publisher: Baker Publishing Group

Published: 2013-11-05T00:00:00+00:00

Major Issues in Translation of the New Testament

As I have already discussed, translations of the Bible have been produced since the earliest days of Christianity. A variety of both translation practices and theories about translation have been propounded. There have been those who have reflected upon translation from Christian times forward. In light of many of the recent translation controversies, some of the comments seem surprisingly progressive, and perhaps they merit further consideration.

Comments on the Nature of Translation

Comments on the nature of translation span the time from the writing of the New Testament to the present, by translators of all types of literature, including (but not limited to) the Bible.96 The range of opinions is worth noting, given what I have discussed above and will discuss below. This list, like the one recounted in the first chapter, constitutes a whirlwind tour of opinions on translation, but the cumulative effect of these voices is relevant to my subsequent discussion, especially in light of the way that some people are advocating for particular theories of translation.

The Latin orator Cicero (106–43 BC), referring to his own translation work, states, “I did not translate them [orations] as an interpreter but as an orator . . . not . . . word for word, but I preserved the general style and force of the language.”97 The Latin poet Horace (65–8 BC), in his Ars Poetica of 20 BC, similarly states, “Nor will you as faithful translator render word for word.” So much for any thought that dynamic and nonliteralistic translations are a recent development!

John Dryden (1631–1700), the poet and literary theorist, in 1680 indicates that there are three types of translation: metaphrase, which is “word for word” and “line for line”; paraphrase, where words are “not so strictly followed as is the sense,” which, he says, “may be amplified but not altered”; and imitation, which he thought may not constitute translation at all. This is reminiscent of a commonly heard distinction between formal, paraphrastic, and dynamic translation.

Alexander Tytler (1747–1813), the Edinburgh professor and friend of Robert Burns, in 1790 defines a “good translation” as “that, in which the merit of the original work is so completely transfused into another language, as to be as distinctly apprehended, and as strongly felt, by a native of the country to which that language belongs, as it is by those who speak the language of the original work.” This formulation consciously notes the role of understanding in translation, to which I will return below.

The poet William Cowper (1731–1800) says in his preface to the Iliad (1791), “The tr[anslation] which partakes equally of fidelity and liberality . . . promises fairest,” akin to the distinction the Holman Christian Standard Bible makes. The German polymath (as well as linguist) Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767–1835) writes in a letter (1796)to the German poet August Wilhelm Schlegel (1767–1845), “All translating seems to me simply an attempt to accomplish an impossible task.” The philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860) recognizes (1851) that “a word in one language seldom has a precise equivalent in another one.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Five People You Meet in Heaven by Mitch Albom(3550)

The Secret Power of Speaking God's Word by Joyce Meyer(3169)

Real Sex by Lauren F. Winner(3012)

Name Book, The: Over 10,000 Names--Their Meanings, Origins, and Spiritual Significance by Astoria Dorothy(2978)

The Holy Spirit by Billy Graham(2942)

0041152001443424520 .pdf by Unknown(2843)

How The Mind Works by Steven Pinker(2811)

ESV Study Bible by Crossway(2773)

Ancient Worlds by Michael Scott(2680)

Churchill by Paul Johnson(2577)

The Meaning of the Library by unknow(2564)

The ESV Study Bible by Crossway Bibles(2547)

The Gnostic Gospels by Pagels Elaine(2527)

MOSES THE EGYPTIAN by Jan Assmann(2411)

Jesus by Paul Johnson(2351)

City of Stairs by Robert Jackson Bennett(2342)

The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English (7th Edition) (Penguin Classics) by Geza Vermes(2270)

The Nativity by Geza Vermes(2226)

Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament by John H. Walton(2221)